The Covenantal Foundation of the Heidelberg Catechism

The Heidelberg Catechism (HC) is one of the most important documents to emerge from the Protestant Reformation. In the space of its 129 questions and answers (Q/As), it beautifully summarizes the Christian faith and life, explaining the gospel with stunning clarity and pastoral warmth. It moves in the logical order of guilt, grace, and gratitude, and exposits three fundamentals of the Christian faith: the Apostles’ Creed, the Ten Commandments, and the Lord’s Prayer. With its combination of profundity, simplicity, and comfort, the HC has brought the light of the Reformation to Christians all over the world for 450 years, providing them with a firm foundation for their faith.

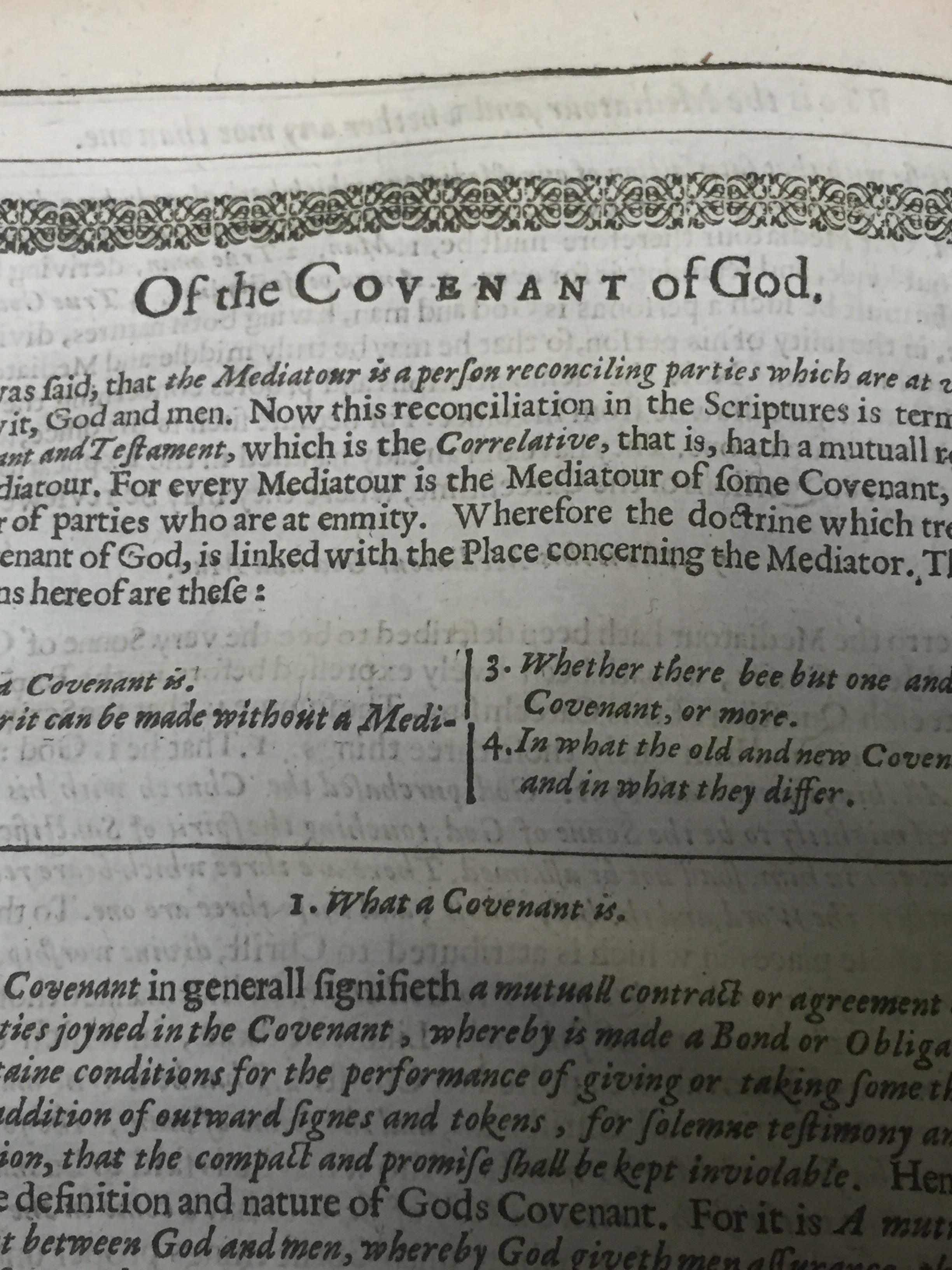

Yet, while the Catechism masterfully teaches essential Christian doctrine, it seems to give very little treatment to covenant (or federal) theology. We may find this troubling since the biblical concept of covenant is central to the Scriptures. Anyone who has read through the Bible even once knows that God’s covenant-making is found throughout its pages with such key figures as Noah, Abraham, the nation of Israel, and David. A covenant, simply defined, is a formal agreement with oaths and promises, creating a solemn relationship between its parties. This is God’s chosen means for relating to humans, and the very essence of Scripture itself. God gave his Word not in the form of a catechism or a series of theological propositions, but in the drama of redemptive history, which unfolds with his covenants.

Two covenants which are critical for our understanding of the gospel are the covenant of works and the covenant of grace. In the covenant of works, God promised glorified life to Adam and all those whom he represented on the condition of Adam’s perfect obedience, and threatened eternal death upon Adam’s disobedience. In the covenant of grace, God promises salvation to sinners through faith in Christ, who merited salvation for his people through his obedience and death.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, reflection on these two covenants became a distinguishing feature among the Reformed. Covenant theology was not an invention by the Reformers. Rather, they built upon the foundations already laid in the patristic and medieval periods.[1] For example, several prominent ancient writers taught a postlapsarian covenant of grace by using the covenant concept to describe the oneness of the historia salutis. “Already in the ancient church,” notes Lyle Bierma, “Irenaeus, Tertullian, Lactactius, and Augustine had all appealed to the covenant idea to support, for various reasons, the basic unity of the Old and New Testaments.”[2] Moreover, some ancient fathers, such as Augustine, also taught a prelapsarian covenant of works.[3]

Building upon this theological groundwork, early Reformers such as Zwingli, Oecolampadius, Bucer, Bullinger, Musculus, and Calvin gave attention to these covenants in order to highlight the gospel, as well as the unity of the Bible.[4] In the 1520s, for example, Zwingli and Oecolampadius began to focus more deliberately on the covenant of grace in response to Anabaptist attacks on the doctrine of infant baptism.[5] By 1534, Bullinger wrote a whole treatise on covenant theology in his De testamento seu foedere Dei unico et aeterno.[6] And in the 1559 edition of his Institutes, Calvin gave treatment to covenant theology in many of its critical and distinctive tenets, particularly the unity of the covenant of grace and the discontinuity of the old and new covenants.[7]

By the mid-seventeenth century, numerous works on covenant theology had been published, and confessions and catechisms with sections on the covenants of works and grace were drafted and adopted. Reformed writers understood that the gospel message recovered during the Reformation would falter without its covenantal foundation.

The prominent role of covenant theology during the Reformation, however, raises a question about the HC: why does it not give attention to the covenants of works and grace as do, for example, its younger British cousins, the Westminster Shorter and Larger Catechisms? In fact, the word “covenant” appears only five times in the HC: twice in Q/A 74, which states that believers’ children are, like their parents, “in the covenant of God” and should receive baptism as “a sign of the covenant;” once in Q/A 77 and again in Q/A 79, where Jesus’ reference to the new covenant in his blood is quoted; and finally in Q/A 82, which warns us against dishonoring “God’s covenant” by admitting unbelievers to the Lord’s Supper. Do these scant references to covenant make the HC deficient as a tool for teaching essential Christian doctrine? Likewise, does the HC’s omission of the covenant of works suggest that this doctrine is a construction of later Reformed theologians?

John Murray (1898-1975) claimed that “the early covenant theologians did not construe [the] Adamic administration as a covenant, far less as a covenant of works.” While acknowledging that the covenant of works was taught by Reformed theologians “towards the end of the 16th century,” and “had come to be interpreted as a covenant, frequently called the Covenant of Works, sometimes a covenant of life or the Legal Covenant,” he maintained that this was not the interpretation of earlier writers. In defense of his thesis, he argued that the

Reformed creeds of the 16th century such as the French Confession (1559), the Scottish Confession (1560), the Belgic Confession (1561), the Thirty-Nine Articles (1562), the Heidelberg Catechism (1563), and the Second Helvetic (1566) do not exhibit any such construction of the Edenic institution. After the pattern of the theological thought prevailing at the time of their preparation, the term ‘covenant,’ insofar as it pertained to God’s relations with men, was interpreted as designating the relation constituted by redemptive provisions and as belonging, therefore, to the sphere of saving grace.[8]

In other words, Murray believed that the major Reformed theologians of the early to mid-sixteenth century held to a covenant of grace, but not a covenant of works. Furthermore, he believed that the HC displayed no evidence whatsoever of teaching a prelapsarian covenant of works.

It is beyond the scope of this essay to examine the covenant theology of every Reformed theologian and confession of the early to mid-sixteenth century in an attempt to see if Murray’s claim holds up. Rather, the purpose of this paper is to challenge Murray’s thesis by arguing that although the appearances of the word “covenant” are sparse in the HC, we should not conclude that it is devoid of a covenantal foundation that employs the covenants of works and grace, for upon closer examination of the catechetical theology of its author, we can safely conclude the very opposite.

The Covenant Theology of Zacharias Ursinus

Zacharias Ursinus (1534-1583), the writer of the HC, played a major role in the development of covenant theology in the sixteenth century.[9] After studying for many years under Melanchthon at Wittenburg, and briefly under Calvin at Geneva, and Bullinger and Vermigli at Zurich, he was invited by the Calvinist Elector Frederick III, ruler of the Palatinate, in 1561 (upon Vermigli’s recommendation) to be the principal of the Sapience College (Collegium Sapientiae), a preparatory academy in Heidelberg.[10] In September of the following year (1562), he was installed as Professor of Dogmatics at the University of Heidelberg. Here he labored until 1568, when he relinquished his post to Jerome Zanchi. He then continued to teach at the Sapience College until 1577, when Lutheranism was restored in the city.[11]

At the time of his installation at the University, Ursinus had already completed two catechisms: the Smaller Catechism (SC), which was designed for children and the general population, and the Larger Catechism (LC), which was designed for lectures to first-year university students.[12] With its 323 questions and answers, the LC is a more thorough explanation of Protestant theology than the SC and HC.[13] Nevertheless, all three of his catechisms – the SC, LC, and HC – have similar structure and methods. As Andrew Woosley puts it, “Ursinus’s method was pedagogical. His aim was always to explain man’s relationship with God.”[14]

What is most striking for our purposes are the LC’s 55 references to covenant in 38 of its Q/As. In fact, the term covenant appears three times in the very first Q/A:

Q.1. What firm comfort do you have in life and in death?

A. That I was created by God in his image for eternal life, and after I willingly lost this in Adam, out of his infinite and gracious mercy God received me into his covenant of grace, so that because of the obedience and death of his Son sent in the flesh, he might give me as a believer righteousness and eternal life. It is also that he sealed his covenant, in my heart by his Spirit, who renews me in the image of God and cries out in me, “Abba, Father,” by his Word and by the visible signs of this covenant.

The similarity to HC Q/A 1 is noteworthy: both catechisms begin by asking the catechumen about his comfort in life and in death, and both answer that it is found in the redemption accomplished by Jesus Christ and applied by the Holy Spirit. The LC, however, specifically connects redemption to the covenant of grace. This is a pattern found throughout its text. For example, Q/As 30-31 state:

Q.30. Where then do you receive your hope of eternal life?

From the gracious covenant that God established anew with believers in Christ.

Q. 31. What is that covenant?

A. It is reconciliation with God, obtained by the mediation of Christ, in which God promises believers that because of Christ he will always be a gracious Father and give them eternal life, and in which they in turn pledge to accept these benefits in true faith and, as befits grateful and obedient children, to glorify him forever; and both parties publicly confirm this mutual promise with visible signs, which we call sacraments.

Like the HC, the LC teaches the Christian faith in the order of guilt, grace, and gratitude. But, as Bierma rightly notes, it “organizes its material around the theme of a twofold covenant – a covenant established at creation and a covenant of grace.”[15]

In its section on man’s guilt and God’s law, the LC describes the law of God as an expression of the covenant God made with Adam in the garden:

Q.10. What does the divine law teach?

It teaches the kind of covenant that God established with mankind in creation, how he managed in keeping it, and what God requires of him after establishing a new covenant of grace with him – that is, what kind of person God created, for what purpose, into what state he has fallen, and how he ought to conduct his life after being reconciled to God.

For Ursinus, the law, given apart from the mediation of Jesus Christ, condemns sinners under the condition of a prelapsarian covenant of works, a “covenant that God established with mankind in creation.” Mankind was subsumed under Adam’s federal headship in this covenant, and subsequently fell with Adam into guilt and condemnation (Q/As 20-29).

Ursinus sharply contrasted the covenants of works and grace, equating the former (which he called the natural covenant [foedus naturale]) with the law, and the latter with the gospel:

Q.36. What is the difference between the law and the gospel?

The law contains the natural covenant, established by God with humanity in creation, that is, it is known by humanity by nature, it requires our perfect obedience to God, and it promises eternal life to those who keep it and threatens eternal punishment to those who do not. The gospel, however, contains the covenant of grace, that is, although it exists, it is not known at all by nature; it shows us the fulfillment in Christ of the righteousness that the law requires and the restoration in us of that righteousness by Christ’s Spirit; and it promises eternal life freely because of Christ to those who believe in him.

The covenant of works (the law) requires perfect obedience to God and promises eternal life to those who keep it. The covenant of grace (the gospel), on the other hand, proclaims Christ’s fulfillment of the law and promises eternal life to all who receive Christ by faith alone. Whereas the covenant of works being made in creation is known inherently by all humans, the covenant of grace is special revelation about Christ, which must be preached to sinners so that they may believe and be saved.

Ursinus made a similar comparison between the law and the covenant of works in Q/A 135 as he expounded on the doctrine of justification by faith alone:

Q.135. Why is it necessary that the satisfaction and righteousness of Christ be imputed to us in order for us to be righteous before God?

Because God, who is immutably righteous and true, wants to receive us into the covenant of grace in such a way that he does not go against the covenant established in creation, that is, that he neither treat us as righteous nor give us eternal life unless his law has been perfectly satisfied, either by ourselves or, since that cannot happen, by someone in our place.

The “covenant established in creation” requires fulfillment of God’s law. Unless this had been accomplished by Christ, righteousness could not be imputed to the believing sinner.

While the law has the primary purpose of teaching the nature of the covenant of works and its principle of “Do this and live,” it still functions in the covenant of grace as a summary of what God requires from believers. Like the HC, the third section of the LC (Q/A 148-263) expounds on the Christian life of gratitude by expositing the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer. It describes the Ten Commandments as a necessary guide for life in the covenant of grace:

Q.148. Do Christians, who have already been received into God’s covenant, also need the teaching of the Decalogue?

Yes, for the law of God must be preached both to those converted through the gospel and to those not yet converted.

Q.150. But why must the law still be proclaimed to the converted after the gospel has been preached?

First, so that they may learn what worship God approves and requires of his covenant partners. Second, so that seeing how far they are in this life from the perfect fulfillment of the law, they may continue in humility and aspire to heavenly life.

Without the law, believers – God’s “covenant partners” – would lack direction and clarity concerning how to please and glorify God in their living.

Likewise, Ursinus describes the practice of prayer as specific to the covenant of grace:

Q.224. Why is the invocation of God necessary for Christians?

First, because it is among the most important parts of the worship of God that the covenant of grace requires of us. Second, because this is the way God wants the elect to acquire and retain both the grace of the Holy Spirit necessary for keeping his covenant and all the rest of his benefits. Third, because it is a testimony in their hearts to the divine covenant. For whoever rightly calls upon God has been given the Spirit of adoption as children and has been received into God’s covenant.

For Ursinus, perseverance in the covenant of grace is impossible apart from prayer.

One notable difference between the LC and HC is the location of their treatments of the ministry of the church, sacraments, and church discipline. In the HC, these subjects are taken up in the second section on grace (specifically in Q/As 65-85), whereas in the LC, Ursinus placed them after the third section on gratitude.[16] Here too, however, Ursinus shows how these vital aspects of the Christian life emerge within the context of the covenant of grace. God instituted the ministry of the church “So that through it he might receive us into his covenant, keep us in it, and really convince us that we are and forever will remain in it” (Q/A 265). The sacraments are “signs of the covenant between God and believers in Christ” (Q/A 274), testifying of “what is promised in the covenant” (Q/A 276). Baptism shows that we have “been received by God into the covenant of grace” (Q/A 284), and the Lord’s Supper “renews the covenant and assures that it will be valid forever” (Q/A 196). Church discipline is necessary so that the “desecration of the sacraments and the divine covenant might be avoided, which occurs when those who by their confession or life show that they are strangers to God’s covenant are admitted to the use of the sacraments” (Q/A 323).

Explicit references are made to the covenants of works and grace throughout the LC, including its first and last Q/As, providing us with a clear view of Ursinus’ covenant theology, and a fuller picture of the covenantal thought present in the mid-sixteenth century.

The Covenant Theology of the Heidelberg Catechism

In 1562, Elector Frederick III ordered the formulation of a new catechism for the Palatinate, the territory of his rule. Such an act was standard practice among Lutheran and Reformed rulers in the sixteenth century.[17] Bierma notes that Frederick had at least three goals in establishing a new catechism for his realm: “it would serve as a catechetical tool for teaching the children, as a preaching guide for instructing the common people in the churches, and as a form for confessional unity among the several Protestant factions in the Palatinate.”[18]

The first of these three goals, namely, the teaching of children in the Palatinate, was of particular concern to Frederick. In his preface to the HC, he mentions his alarm by the spiritual condition of the youth in the Palatinate churches:

Therefore we also have ascertained that by no means the least defect of our system is found in the fact, that our blooming youth is disposed to be careless in respect to Christian doctrine, both in the schools and churches of our principality – some, indeed, being entirely without Christian instruction, others being unsystematically taught, without any established, certain, and clear catechism, but merely according to individual plan or judgment; from which, among other great defects, the consequence has ensued, that they have, in too many instances, grown up without the fear of God and the knowledge of His word, having enjoyed no profitable instruction, or otherwise have been perplexed with irrelevant and needless questions, and at times have been burdened with unsound doctrine.[19]

This helps explain why the HC is simple and concise in comparison to the LC. It has only 129 Q/As in contrast to the LC’s 323, and uses less technical language because it was crafted with the specific purpose of instructing children.

The less technical language of the HC is also due to the fact that Frederick wanted a catechism that could more easily unite the various Protestant factions within his realm. Bierma points out that in Frederick’s preface to the HC, “never once does he mention Melanchthon, Calvin, Beza, or Bullinger. Instead, he speaks in broad terms of ‘Christian doctrine,’ ‘Christian instruction,’ ‘the pure and consistent doctrine of the holy Gospel,’ and a ‘catechism of our Christian religion, according to the Word of God.’” As concerned as he was with the theological instruction of children, Frederick had a political motive as well: the peace and unity of the Palatinate:

When one takes into account the existence of several Protestant parties in Heidelberg, the diversity of catechisms in use in the Palatinate in the early 1560s, Frederick III’s doctrinal conflicts with the Gnesio-Lutherans, differences in the understanding of the Lord’s Supper reflected at the “Wedding Debates,” the recent confessional status of the ubiquity doctrine, and the disunity among the Protestant princes at the Naumburg Colloquy, it is hardly surprising that Frederick would commission a new catechism as a standard preaching and teaching guide around which the major Protestant factions in his realm could unite.[20]

These facts shed some light on the HC’s infrequent use of the term “covenant.” It was not Frederick’s goal to produce an elaborate catechism for theological students with terms and language that might prove cumbersome for children, as well as threatening to the union of Protestant groups in the Palatinate.[21]

Bierma speculates that the absence of the covenant of works in the HC is due to a “process of theological maturation,” in which Ursinus avoided explicit references to “a doctrine that he was only beginning to think through.”

The fact that the LC was never published in Ursinus’ own lifetime, that it appeared in print posthumously against his earlier wishes, that covenant is given less prominence and a different accent in his later lectures, and that he never again referred to a natural covenant in his later works all suggest a measure of development in his thought on this point.[22]

This theory, however, is unconvincing for several reasons. First, it does not do justice to the short duration of time between the writing of the LC and the HC. Given that both catechisms were written within the space of one to two years, it is unreasonable to conclude that the HC represents a more mature theology in Ursinus. Second, it fails to explain why Ursinus toned down the language of the covenant of grace in the HC. If the absence of a covenant of works in the HC demonstrates a “process of theological maturation,” should we not then conclude the same with regard to the catechism’s scant references to the covenant of grace? Third, there is no evidence that Ursinus retracted any of the covenant theology expressed in his LC, or that he ceased using the LC as lecture material after the publication of the HC. Finally, and perhaps most problematic to Bierma’s conjecture, is that the SC, being specifically designed for children, contains only three references to “covenant,” and was written before the LC.[23] This militates against the theory that the HC’s omission of the covenant of works represents a more mature theology in Ursinus. Conversely, it supports the hypothesis that the HC contains less references to covenant chiefly because it was composed for children. This seems even more likely when we consider that no fewer than 90 of the SC’s Q/As are found in 110 of the Q/As in the HC. Ursinus seemed to use the SC – his earlier children’s catechism – as a template for the HC.

Thus, there is no reason to conclude that a theological tension exists between the HC and the LC. Both were written by the same author within the space of a few years. Recent scholarship has shown that while the HC was commissioned by Frederick and may have involved leading theologians of the Palatinate (such as Caspar Olevianus), its final draft was more than likely the sole responsibility of Ursinus.[24] In his 1562 inaugural address, at which time his LC was already completed, Ursinus mentioned that “the territorial catechism currently in preparation was just about ready.”[25] Moreover, the similarity between the two catechisms (as well as Ursinus’ SC), with their parallel language, order of guilt, grace, and gratitude, expositions of the Apostles’ Creed, Ten Commandments, and Lord’s Prayer, is remarkable. Despite the HC’s limited references to the word “covenant,” there is nothing in its text that suggests Ursinus departed from the covenant theology expressed in his LC and which he taught at the University and College for many years.

In fact, the HC is very much a product of Ursinus’ covenant theology. Q/A 74, which roots baptism in the covenant of grace, is evidence of that fact. Additionally, Ursinus makes references to covenant throughout his Commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism, including an excursus devoted to the covenant of God in his comments under Q/A 18.[26]

Yet, even in places where his Commentary does not use the term “covenant” explicitly, we are able to see Ursinus’ covenant theology in operation. For example, in his comments on the law of God under Q/A 92, Ursinus says,

The moral law is…known by nature, engraven upon the hearts of creatures endowed with reason in their creation…teaching what God is and what he requires, binding all intelligent creatures to perfect obedience and conformity to the law, internal and external, promising the favor of God and eternal life to all those who render perfect obedience, and at the same time denouncing the wrath of God and everlasting punishment upon all those who do not render this obedience.[27]

This is nearly identical language to LC Q/A 36, which equates the law with the covenant of works – what Ursinus calls the natural covenant (foedus naturale): “The law contains the natural covenant, established by God with humanity in creation, that is, it is known by humanity by nature, it requires our perfect obedience to God, and it promises eternal life to those who keep it and threatens eternal punishment to those who do not.” Similar parallels can be found throughout his Commentary.

Indeed, the HC as a whole emerges as a structure built upon the foundations of covenant theology. Its section on man’s sin and misery (Q/A 3-11) is essentially a description of the catastrophic consequences of Adam’s violation of the covenant of the works. Its exposition of the Apostles’ Creed and the doctrine of justification (12-64) is a summary of the covenant of grace and all the benefits believers receive through its Mediator, the Lord Jesus. Its treatment of the means of grace and the ministry of the church (65-85) explains how God receives believers into his covenant of grace and causes them to persevere in faith. Its teaching on Christian gratitude, which unpacks the Ten Commandments and Lord’s Prayer (86-129), provides believers with God’s prescribed pattern for their lives as members of his covenant.

Conclusion

The HC’s omission of the covenant of works fails to prove Murray’s thesis that “the early covenant theologians did not construe [the] Adamic administration as a covenant, far less as a covenant of works,” and that this was only a construction of Reformed theologians “towards the end of the 16th century.”[28] A cursory examination of Ursinus’ LC reveals just the opposite. Murray, who himself rejected the doctrine of the covenant of works, either overlooked or did not have access to the LC. Little else seems to explain why he would make the claim that “the covenant theologians who followed Calvin, such as Jerome Zanchius, Zachary Ursinus, and Caspar Olevianus…do not orient their exposition [of the covenant of grace] to a comparison and contrast with the Covenant of Works, as later theologians were wont to do.”[29] As shown above, Ursinus in fact makes sharp comparisons and contrasts between the covenants of works and grace in LC Q/As 10, 36, and 135. In sum, Ursinus was not the kind of covenant theologian whom Murray made him out to be. Rather, he had far more continuity with later covenant theologians than Murray asserted.

Furthermore, a comparison of the HC to the LC reveals the covenantal roots of the former. Like an iceberg that has only ten to twenty percent of its mass above the waterline, the HC exposes only a fraction of the theology upon which it is built, a wise approach for any teaching tool designed for children. It provides catechumens with the basics of Christianity: God saves guilty sinners by his grace alone, through faith alone, because of Christ alone, and calls them into a life of gratitude. It is for this reason that it remains to this day one of the warmest comforts and brightest lights of the Reformation. Yet, just beneath its surface stands the massive foundation upon which it is built: God’s covenant with us, mediated through the person and work of Jesus Christ.

*This essay by Michael Brown, pastor of Christ URC in Santee, CA, was published in the Puritan Reformed Journal, vol.7, no. 1, January 2015

[1] See, for example, chapters 5-7 of Andrew A. Woolsey, Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought: A Study in the Reformed Tradition to the Westminster Assembly (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2012, which explores the covenant in patristic, medieval, and early Reformation thought.

[2] Lyle D. Bierma, German Calvinism in the Confessional Age (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996), 168.

[3] “But even the infants, not personally in their own life, but according to the common origin of the human race, have all broken God’s covenant in that one in whom all have sinned…For the first covenant, which was made with the first man, is just this: ‘In the day ye eat thereof, ye shall surely die.’” City of God, Great Books of the Western World, ed. Mortimer Adler, trans. Marcus Dods (Reprint, London: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952), 18:439.

[4] On the development of covenant theology among the sixteenth century Reformers, see, among others, Woolsey, Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought; Peter A. Lillback, The Binding of God: Calvin’s Role in the Development of Covenant Theology, Texts and Studies in Reformation and Post-Reformation Thought, ed. Richard A. Muller (Grand Rapids: Baker, Carlisle, UK: Paternoster, 2001); Bierma, “The Role of Covenant Theology in Early Reformed Orthodoxy,” Sixteenth Century Journal 21 (1990): 453-462; Michael Brown, Christ and the Condition: The Covenant Theology of Samuel Petto (1624-1711), (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2012), 43-85.

[5] See Huldrych Zwingli, Samtliche Werke, eds., Emil Egli et al., vol. 93 of Corpus Reformatorum [CR] (Munich: Kraus Reprint, 1981), 156-70; Selected Writings of Huldrych Zwingli, trans. E. J. Furcha and H. Wayne Pipkin, 2 vols. (Allison Park, PA: Pickwick Publications, 1984), 1:106. J.W. Cottrell has argued that Zwingli was using covenant language as early as 1522, well before his noted debates with the Anabaptists. See Cottrell, “Covenant and Baptism in the Theology of Huldreich Zwingli (ThD diss., Princeton Theological Seminary, 1971), 81. As Bierma notes, however, it was particularly in his 1525 “Reply to Hubmeir” and 1527 “Refutation of the Tricks of the Anabaptists” that Zwingli defended the practice of baptizing the children of believers on the grounds of the one, unifying covenant of grace in redemptive history. See Bierma, German Calvinism in the Confessional Age, 31-35.

[6] An English translation of this is published in Charles S. McCoy and J. Wayne Baker, Fountainhead of Federalism: Heinrich Bullinger and the Covenantal Tradition With a Translation of De Testamento Seu Foedere Dei Unico Et Aeterno (1534) (Louisville: Westminster, 1991), 99-134.

[7] See Institutes, 2.7-11, 4.16. See also J.V. Fesko, “Calvin and Witsius on the Mosaic Covenant,” in The Law Is Not of Faith: Essays on Grace and Works in the Mosaic Covenant, eds., Bryan D. Estelle, J.V. Fesko, and David VanDrunen (Philipsburg, N.J.: P&R, 2009), 25-43; Lillback, “Calvin’s Interpretation of the History of Salvation: The Continuity and Discontinuity of the Covenant,” in A Theological Guide to Calvin’s Institutes: Essays and Analysis, ed. David W. Hall and Lillback (Phillipsburg, N.J.: P&R, 2008), 168-204; and Brown, Christ and the Condition, 47-51.

[8] John Murray, “Covenant Theology,” in Collected Writings of John Murray vol.4 (Edinburgh, UK: Banner of Truth, 1982), 217-18.

[9] See August Lang, Der Heidelberger Katechismus und vier verwandte Katechismen (Leipzig: Deichert, 1907); Derk Visser, “The Covenant in Zacharias Ursinus,” Sixteenth Century Journal 18 (1987); David A. Weir, The Origins of the Federal Theology in Sixteenth-Century Reformation Thouhgt (Oxford: Clarendon, 1990), 99-114; Biersma, “Law and Grace in Ursinus’ Doctrine of the Natural Covenant: A Reappraisal” in Protestant Scholasticism: Essays in Reassessment (Carlisle, UK: Paternoster Press, 1999), 96-110;

[10] The Palatinate was a large territory in the Rhineland of Germany. It was one of the leading principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, a region encompassing the modern-day countries of Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic as well as parts of Italy, France, and Poland.

[11] For biographical information about Ursinus see: J.W. Nevin, “Zacharias Ursinus,” Mercersburg Review 3 (1851): 490-512; D. Visser, Zacharias Ursinus: The Reluctant Reformer (New York, 1983); Andrew A. Woolsey, Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought: A Study in the Reformed Tradition to the Westminster Assembly (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2012), 399-400; Lyle D. Bierma, An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism: Sources, History, and Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 67-74.

[12] Ursinus’ Larger Catechism is also known as his Catechesis, Summa Theologiae and Catechesis maior.

[13] Ursinus wrote it sometime in 1561/2, but it did not appear in print until the year after his death, in 1584. See Zacharias Ursinus, Opera Theologica, 3 vols., ed. Quirinus Reuter (Heidelberg: Lancellot, 1612), 1:10-11.

[14] Woosley, Unity and Continuity in Covenantal Thought, 403.

[15] Bierma, An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism, 139.

[16] The SC, on the other hand, unfolds in a fashion almost identical to the HC: summary of the law and our misery (Q/A 7-10), the Apostles’ Creed (13-44), the sacraments (53-71), the Ten Commandments (72-95), and the Lord’s Prayer (96-108).

[17] Bierma, An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism, 49. “During the early years of the Reformation, numerous confessions and catechisms appeared, totaling hundreds of pages in modern collections of these works. Even in the Palatine itself several Lutheran and Reformed catechisms were in use at the time Heidelberg Catechism was commissioned. What is surprising, therefore, is not so much that the Palatine created its own catechism but that it had not done so earlier.”

[18] Ibid., 51.

[19] As found in George W. Richards, The Heidelberg Catechism: Historical and Doctrinal Studies (Philadelphia: Publication and Sunday School Board of the Reformed Church in the United Sates, 1913), 191.

[20] Bierma, An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism, 52.

[21] Bierma notes that “according to the Peace of Augsburg (1555), all non-Catholic princes and territories of the German Empire were required to adhere to Lutheranism as defined by the Augsburg Confession; no other varieties of Protestantism were permitted. In designing a new catechism for the Palatinate, therefore, Frederick III found himself in a delicate position. How could he as a Lutheran elector confessionally repudiate Gnesio-Lutheran doctrines that he found objectionable and unify the Melanchthonian-Lutheran, Calvinist, and Zwinglian factions in his realm without straying outside the bounds of the Augsburg Confession and thus violating the terms of the Peace of Augsburg? His answer was the HC…What we find in the HC is doctrinal outer boundaries, on the one hand, and common ground and key silences within those boundaries, on the other.” Ibid., 78. It should also be noted that Frederick appeared before the Holy Roman Emperor at the diet of Augsburg in 1566, Elector August of Saxony defended him by arguing that the HC was no more beyond the boundaries of the Augsburg Confession than Brenz’s Gnesio-Lutheran Stuttgart confession of 1599. See Fred H. Klooster, The Heidelberg Catechism: Origin and History (Grand Rapids: Calvin Theological Seminary, 1981), 97.

[22] Bierma, An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism, 98. See also his “Law and Grace in Ursinus’ Doctrine of the Natural Covenant: A Reappraisal,” in Trueman and Clark [eds.], Protestant Scholasticism (Carlisle, UK: Paternoster Press, 1999), 101-2.

[23] The SC has one reference in Q/A 55 on the sacraments, Q/A 63 on infant baptism, and Q/A 71 on the Lord’s Supper. It also mentions “testament once in Q/A 67 and three times in Q/A 69, both of which refer to the Lord’s Supper.

[24] See Bierma’s research in An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism, 52-74.

[25] See Bierma, Ibid., 138. This is based on a discovery by Erdmann Sturm in 1972.

[26] Ursinus, The Commentary of Dr. Zacharias Ursinus on the Heidelberg Catechism, trans. by G.W. Williard (Phillipsburg, N.J.: P&R, 1992), 96-100. These were the substance of his lectures on the HC.

[27] Ursinus, Commentary, 490-91.

[28] Murray, “Covenant Theology,” 217-18.

[29] Murray, “Covenant Theology,” 225.